Buy Now, Pay Later

- – 4-month term

- – No impact on credit

- – Instant approval decision

- – Secure and straightforward checkout

Ready to go? Add this product to your cart and select a plan during checkout.

Payment plans are offered through our trusted finance partners Klarna, Affirm, Afterpay, Apple Pay, and PayTomorrow. No-credit-needed leasing options through Acima may also be available at checkout.

Learn more about financing & leasing here.

This item is eligible for return within 30 days of receipt

To qualify for a full refund, items must be returned in their original, unused condition. If an item is returned in a used, damaged, or materially different state, you may be granted a partial refund.

To initiate a return, please visit our Returns Center.

View our full returns policy here.

Description

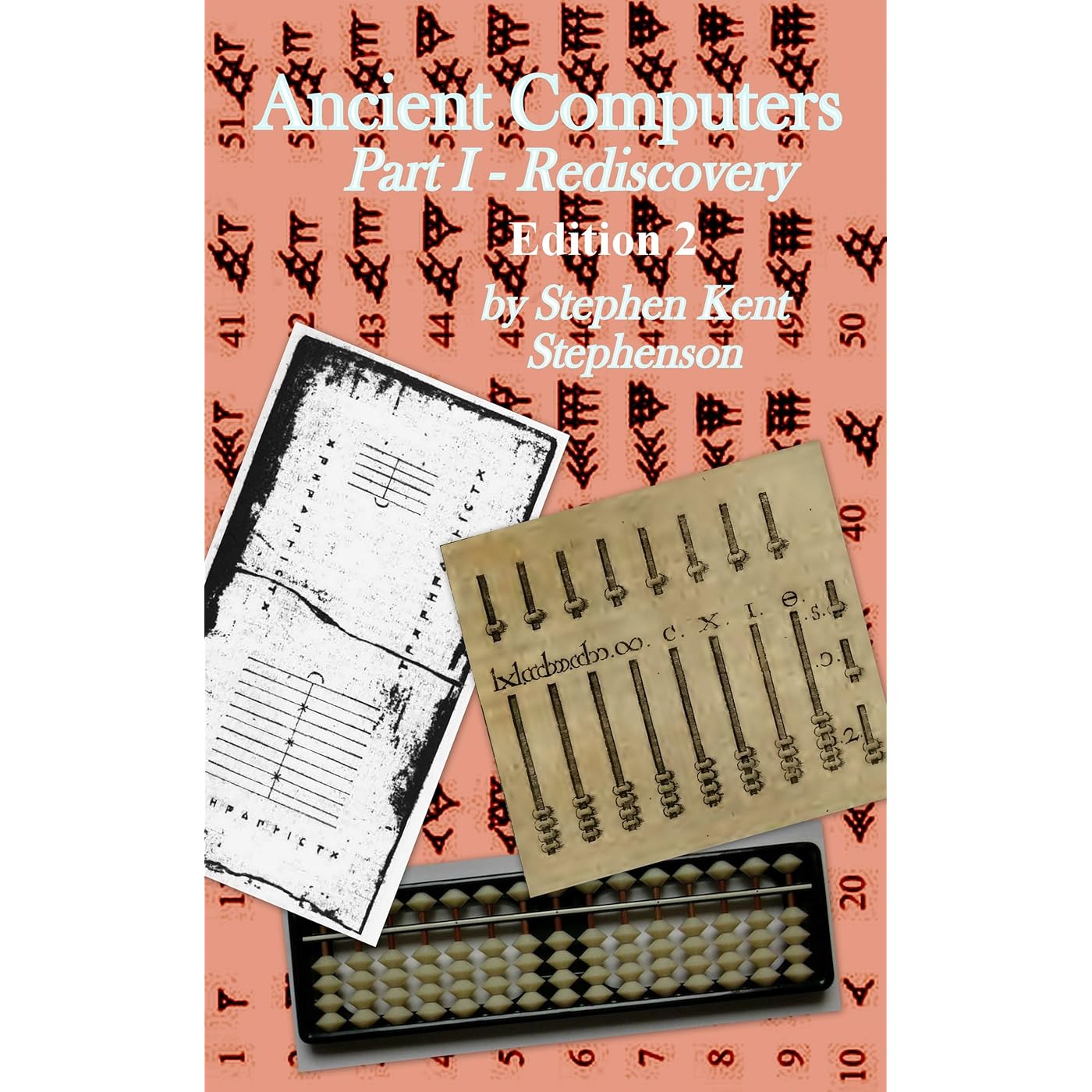

Ancient Computers is an excellent introduction to the calculating methods of diverse cultures across time. A mixture of history and practical techniques for understanding and using these ancient devices brings the tools of these long-forgotten civilizations to a wide audience. Stephenson writes in an easy- to-understand and accessible manner and the use of diagrams is extensive. Want know how to use an abacus or where it came from? This is the book for you! The book is appropriate for high school audiences and above. Dag Spicer Senior Curator Computer History Museum Mountain View, CA ===== The author ... makes two points that deserve wider dissemination. The first is that he sees the central dividing line of the Salamis Tablet as allowing an additive side and a subtractive side ... and notes that this approach, ‘reduces the number of pebbles needed tremendously’. It also makes many calculations easier. One cannot argue with his claims of increased efficiency and this point deserves further investigation. The author’s second substantive point is that in attempting to understand ancient mathematics, historians need to pay more attention to the available tools, technology, notation, and terminology to see how particular algorithms may have been performed. The author has a video of himself computing the square root of 2 using a set of Salamis Tablets following Heron's method. It takes him 25 minutes [to achieve the four sexagesimal digit precision of Yale tablet YBC 7289]. His argument is that [making and] using only [mathematical reference] tables and writing intermediate [cuneiform] results on clay would take a lot longer. From review by Prof. Duncan Melville, in Aestimatio, ===== People, especially historians, have long struggled to appreciate and understand how Ancient Romans, Greeks, Egyptians, and Babylonians, et al, were able to do their arithmetic calculations. Many say the Ancients "probably" used line abacuses or abaci, a.k.a. counting boards. But most then trivialize the possible impact that use would have on the Ancient cultures because they really don't think those abaci would be very powerful and that they would be extremely hard to use. The (re-)discovery this book documents and explores materialized from the author's experiences in engineering, with a knowledge that design compromises often have to be made; computer programming, especially the different number bases used; the hobby use of a Japanese abacus called the Soroban; and study of the Ancients' numbers and culture. The bottom line is that the Ancients had a powerful and lightning fast computer; powerful and fast compared to any other calculation method available to them in their time. Features included: - multi-base number modes: e.g., sexagesimal, decimal, duodecimal, or nonary; - operating on those numbers in two parts: a signed fraction of the base and a signed exponent of the base, equivalent to scientific notation; - easy and low-cost expandability; and - built-in error checking! On the "standard" Ancient line abacus doing base-10 calculations, the fraction could have 10 significant digits and the exponent 4. Certainly enough for most modern engineering or scientific problems. If you need more, though, just scribe a few more lines on the abacus and add a few more pebbles to your pouch! By the way, 170 small pebbles will suffice for any problem on the "standard" line abacus. They fit in a pouch that can be easily and comfortably carried in a man's trouser pocket. I hope you find Ancient Computers interesting and useful, -Steve Stephenson, July 15, 2010 ===== Edition 2 corrects some formatting issues and adds two appendices: N: Nonary Abacus as Candidate for Modern Electronic Implementation; and V: Visualizing the Basis of Abacus Arithmetic using Colored Chip Models. -Steve Stephenson, July 15, 2013 Read more

Publisher : Stephen Kent Stephenson

Accessibility : Learn more

Publication date : November 19, 2013

Edition : 2nd

Language : English

File size : 1.9 MB

Simultaneous device usage : Unlimited

Screen Reader : Supported

Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

Frequently asked questions

To initiate a return, please visit our Returns Center.

View our full returns policy here.

- Klarna Financing

- Affirm Pay in 4

- Affirm Financing

- Afterpay Financing

- PayTomorrow Financing

- Financing through Apple Pay

Learn more about financing & leasing here.